Pediatric pain medications

When children are in the hospital, they often need pain relief or sedation, yet most drugs used for pain relief or sedation in children have not been studied in children. A first step in understanding the overall use of pain medications is to document the medications used and their frequency of use. Our publication, “Use of Analgesic, Anesthetic, and Sedative Medications During Pediatric Hospitalizations in the United States 2008”, published in the journal, Anesthesia and Analgesia in 2012, describes medications used in over 800,000 hospitalizations.

We describe use of analgesics, anesthetics, and sedatives in pediatric inpatients by conducting a statistical analysis of medication data from the Premier database. We identified all uses of a given medication, selected the first use for each child, and calculated the prevalence of use of specific medications among hospitalized children in 2008 as the number of hospitalizations in which the drug was used per 100 hospitalizations. Dose and number of doses were not considered in these analyses.

The dataset contained records for 877,201 hospitalizations of children younger than 18 years of age at the time of admission. Thirty-three medications and an additional 11 combinations were administered in this population, including nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, local and regional anesthetics, opioids, benzodiazepines, sedative-hypnotics, barbiturates, and others. The 10 most frequently administered analgesic, anesthetic, or sedative medications used in this population were acetaminophen (14.7%), lidocaine (11.0%), fentanyl (6.6%), ibuprofen (6.3%), morphine (6.2%), midazolam (4.5%), propofol (4.1%), lidocaine/ prilocaine (2.5%), hydrocodone/acetaminophen (2.1%), and acetaminophen/codeine (2.0%).

Use changed with age, and the direction of change (increases and decreases) and the type of change (linear, u-shaped, or other) appeared to be specific to each drug.

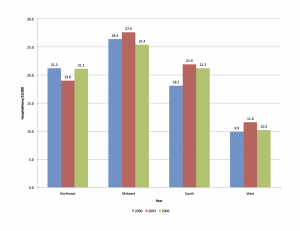

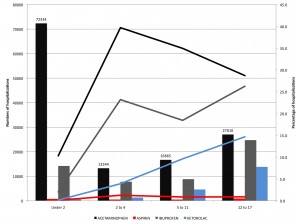

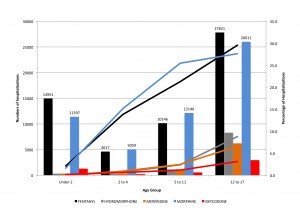

Figure 1 shows the number and percentage of pediatric hospitalizations with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) use, by age group. Bars indicate number of hospitalizations. Lines indicate percentage of hospitalizations. Acetaminophen was considered in these analyses as an NSAID for the sake of categorical simplicity; however, pharmacologically, the antiinflammatory activity of acetaminophen is minimal, such that some do not consider it a true NSAID.

Figure 1. Number and percentage of pediatric hospitalizations with non steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, by age group.

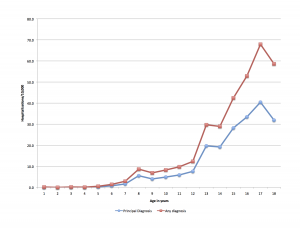

Figure 2 shows the number and percentage of pediatric hospitalizations with opioid use, by age group. Bars indicate number of hospitalizations. Lines indicate percentage of hospitalizations.

Figure 2. Number and percentage of pediatric hospitalizations with opioid use, by age group.

See the accompanying editorial by Joseph Tobin, MD, “Pediatric Drug Labeling: Still an Unfinished Need”. As he says,

Chronic pain in children is seriously underrecognized in comparison with the prevalence of chronic pain in adults. This is one more circumstance in which labeling in children would be very beneficial to anesthesiologists and their patients.