“Studying medicines in children is always possible and is in their best interests”

A sentiment that can’t be repeated often enough.

The Council of Canadian Academies just released their report, Improving Medicines for Children in Canada, and while the title indicates a focus on Canada, much of the report is relevant to goal of improving medicines for children everywhere.

Children have historically been excluded from clinical trials and drug research to protect them from the risks of research.

As a result, there is a lack of information about medicines and how they affect children at different ages and stages of development. Throughout, the panel stresses the importance of including children in research,

The assumption that children must be protected from research is misguided. Children should be protected through research. Despite the many challenges to research with children, a range of methods and designs are increasingly accepted as ethically and scientifically sound. Demonstrating safety and efficacy of a medicine in studies with children is always feasible and desirable. It is now globally recognized that the medical community, the pharmaceutical industry, and regulatory agencies have an ethical responsibility to design, conduct, and report on high-quality studies of medicines in children.

Key findings

As with so much of the report, the key findings are applicable in the US, Europe and elsewhere. As they note,

- Children take medications, many of which have not been proven safe and effective for their use.

- Children respond to medications differently from adults; thus, medicines must be studied in children and formulated for children.

- Studying medicines in children is always possible and is in their best interests.

The panel reviewed a comprehensive body of information and brings together relevant science from several disciplines. As such, it provides a cogent synthesis of the many issues around pediatric medication use. It begins with a description of the current environment and regulations, variation in children’s response to medications, issues around formulation, and covers current approaches to studying efficacy in children, monitoring and studying the safety of drugs used by children, and a thoughtful discussion around practices to support safe and effective products for children.

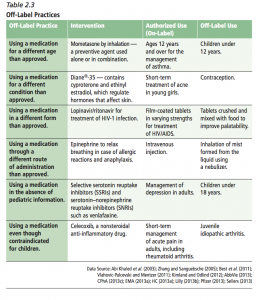

Off-label use

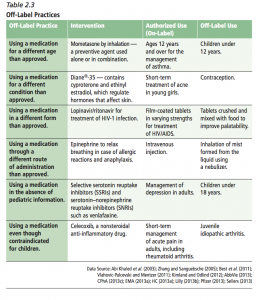

The overview of the current environment provides this useful chart summarizing different types of off-label practices, with examples of both the authorized (on-label) and off-label use.

Off-label practices

Variability in response to medications

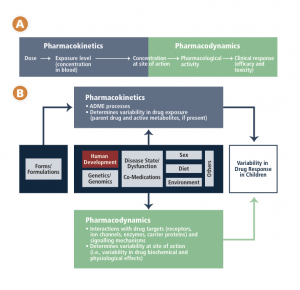

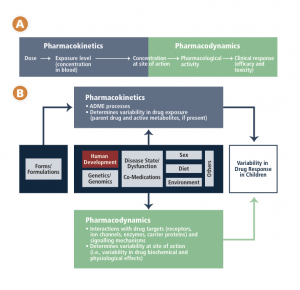

Chapter 3 includes this schematic of the factors affecting variability in children’s responses to medications.

CCA schematic – drug response in children

They return to this issue in their conclusions, as they underscore the affect of human development from infancy to youth, and its affect on clinical pharmacology,

As children progress from infancy through to adolescence, a number of significant developmental changes occur. These changes impact how their bodies deal with medications (pharmacokinetics) and how medications, in turn, affect their bodies (pharmacodynamics). These factors cannot be accommodated by simply adjusting an adult dose. The physiological systems that process drugs change over time, with the most dramatic age-related physiological changes taking place during the first year of life. A newborn will respond to a drug differently than an adolescent will, and this variability in response is not a linear progression but rather a dynamic process dependent on age, weight, the drugs and conditions involved, and individual and environmental factors.

The report concludes with a fervent call to action,

Children’s right to health includes a right to medicines that are well-studied and approved for use in their age group. Children deserve timely and equitable access to safe and effective treatments and care, including participation in research.

The Expert Panel on the State of Therapeutic Products for Infants, Children, and Youth was chaired by Dr. Stuart MacLeod, Professor of pediatrics at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.