“One Drug or 2? Parents See Risk but Also Hope”, a recent article in the NYTimes, caught my attention because of its focus on pediatric medication use.

The article portrays the issues around the decision to add an antipsychotic medication, Risperdal, to a daily regime of Adderall for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and begins with a story about Matthias, 6 years old.

The article describes the mother’s dilemma,

Her dilemma is shared by a steadily rising number of American families who are using multiple psychotropic drugs — stimulants, antipsychotics, antidepressants and others — to temper their children’s troublesome behavior, even though many doctors who mix such medications acknowledge that little is known about the overall benefits and risks for children.

It describes a family with a child who has not responded to the guideline recommended treatment of methylphenidate combined with behavioral therapy, and interviews physicians to find out their opinions about the treatment options. One psychiatrist interviewed, underscored the lack of evidence and and anecdotal nature of decision making when there is no evidence, saying, “When I prescribe multiple psychotropics, there’s a good reason — even if I don’t know the exact interactions or efficacy, there’s a clinical reason to give it a shot,” said Dr. J. Wesley Boyd, a psychiatrist at the Cambridge Health Alliance in Massachusetts. “But saying, ‘The last time I gave x, y and z to someone they did fine,’ that’s not science.” Another physician is quoted as cautioning the mother, “We’re really feeling around in the dark with this stuff.” He followed up by saying that he had never prescribed both medications to a child so young.

Questions are raised by this story

First of all, the glaring lack of evidence to inform clinical decisions and support evidence-based medicine.

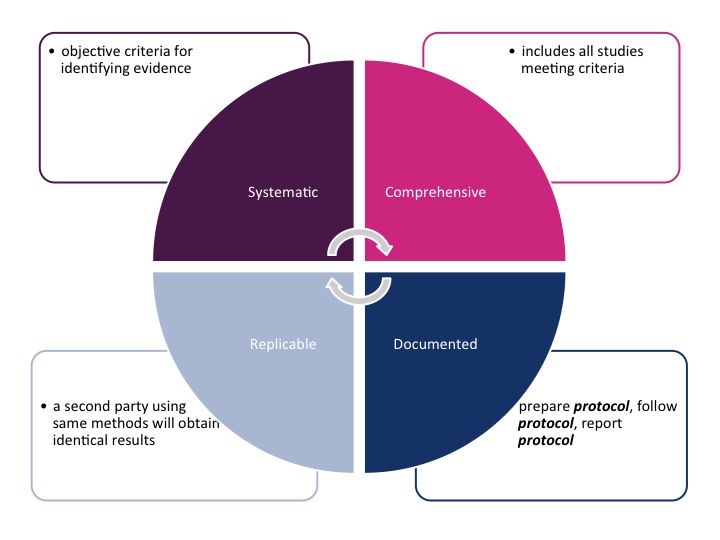

Evidence based medicine means just that – a treatment or other medical procedure is studied, the evidence is weighed, and guidelines are developed to help providers decide on the best course for each patient. Unfortunately, we are without an evidence base for many medications used in children. Children have historically been excluded from clinical trials to protect them from research risks. This policy has been reversed in the past 10 or 20 years after realizing that children have not been served by this policy and that children are being treated with medications without an evidence base or guidelines to inform practice.

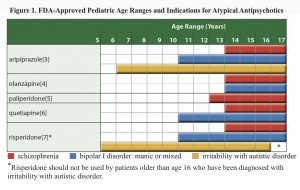

To clarify what this means, the pediatric labeling for Adderall (the first drug used to treat Matthias) is based on one study of 584 children with ADHD (age 6-12) for three weeks and on a second study of 51 patients (age and duration of the study not specified). Risperidone (the second drug being considered to treat Matthias) has been study in children age 13-17 with schizophrenia, age 10-17 with bipolar disorder, in combination with lithium or valproate for acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar disorder, and in children age 5-17 with autistic disorder.

Second, the wide-spread off-label use of medications

One clinician quoted in the article says, “You cannot tell the family, ‘Come back in five years and we’ll treat you with this medication’ until the F.D.A.’s going to approve it.” The physician is referring to the lack of FDA labeling or approval to use the medication in children. When there is a lack of evidence for an indication or specific age group, FDA cannot approve the medication for that use. When clinicians believe that the drug should be used, despite the lack of evidence, this is termed “off-label” use. As the AAP notes in their press release along with the release of their policy statement, “Off-Label Use of Drugs in Children”,

“Pediatricians must prescribe drugs off-label, simply because an overwhelming number of critical drugs still have no information on the label for use in children”

AAP statement on off-label prescribing

The AAP policy statement proceeds to address ethical and legal concerns practitioners may have about off-label use of medications. The policy statement begins by saying, “The use of a drug, whether off or on label, should be based on sound scientific evidence, expert medical judgment, or published literature whenever possible.” For the reader, lack of evidence and lack of FDA approval are not identical, although evidence should lead to labeling, and lack of labeling suggests a lack of evidence. It is not clear what types of off-label use might meet the AAP criteria of sound scientific evidence, expert medical judgment and published literature in the absence of enough evidence to support practice.

If there is no evidence, is off-label use research? AAP policy states,

In most situations, off-label use of medications is neither experimentation nor research. The administration of an approved drug for a use that is not approved by the FDA is not considered research and does not warrant special consent or review if it is deemed to be in the individual patient’s best interest. In general, if existing evidence supports the use of a drug for a specific indication in a particular patient, the usual informed-consent conversations should be conducted, including anticipated risks, benefits, and alternatives. If the off-label use is based on sound medical evidence, no additional informed consent beyond that routinely used in therapeutic decision-making is needed. However, if the off-label use is experimental, then the patient (or parent) should be informed of its experimental status.

Again, it would be very helpful to have clarification on when the off-label use is considered to be experimental, and perhaps some examples or guidelines.

What about the legal issues? AAP policy recommends,

… because the use of drugs in an off-label capacity can increase the liability risk for a practitioner should an adverse event or poor outcome ensue, it is essential that practitioners document the decision-making process to use a drug off label in the patient’s medical record.

The level of detail and type of documentation is not specified.

So, what about the evidence?

FDA approvals for anti-psychotics in children

Neither the journalist nor the physicians interviewed mentioned any of evidence regarding the treatment decision, and while the evidence base is inadequate some evidence exists. Several reports have emerged in the literature describing the use of respiridone in addition to stimulants (methylphenidate) to manage ADHD, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality published an extensive review, “First- and Second-Generation Antipsychotics for Children and Young Adults” summarizing the evidence around pediatric use of anti-psychotics. With over 156 pages plus appendices and state-of-the art systematic review methodology, the authors’ search strategy identified 10,745 citations, of which, 140 articles met the inclusion criteria, and 81 were unique studies. They reported low to moderate evidence that second generation anti-psychotics had beneficial effect on ADHD and disruptive behavior disorder (Table B). They also reported information about adverse events showing low to moderate quality evidence that placebo and anti-psychotic produce no differences for some adverse events, and favor placebo for others. The review excluded studies of combination treatments and does not directly inform the decision whether to add an anti-psychotic to the adderal regimen.

Resources

ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management, Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, DuPaul G, Earls M, Feldman HM, Ganiats TG, Kaplanek B, Meyer B, Perrin J, Pierce K, Reiff M, Stein MT, Visser S. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011 Nov;128(5):1007-22.

Aman et al, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, January 2014 “What Does Risperidone Add to Parent Training and Stimulant for Severe Aggression in Child Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder?”

Atypical Antipsychotic Medications: Use in Pediatric Patients CMS Fact Sheet 2013

Gadow et al, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, September 2014 “Risperidone Added to Parent Training and Stimulant Medication: Effects on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Conduct Disorder, and Peer Aggression”

Seida JC, Schouten JR, Mousavi SS, Hamm M, Beaith A, Vandermeer B, Dryden DM, Boylan K, Newton AS, Carrey N. First- and Second-Generation Antipsychotics for Children and Young Adults. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 39. (Prepared by the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10021.) AHRQ Publication No. 11(12)-EHC077-EF. Rockville, MD. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. February 2012.