The recent Ebola cases and fatality have triggered a collective process of finger pointing as we struggle to understand events and hold someone accountable.

Hence, the television footage of health officials hauled off to Congress, accusatory headlines (“Alarming stumbles by the C.D.C.”) and appointment of czars. In the desire to pin the blame somewhere, notably the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), we overlook the essential fact that in the United States public health responsibilities are fragmented among federal agencies, and decentralized throughout state and local government. The laws and regulations governing public health activities at federal, state and local levels is truly wonky terrain, but understanding these details is critical to being able to improve our response to public health emergencies. We need to know who actually has the authority to deal with specific public health functions and who should be held accountable (spoiler alert – it is not the Czar, nor the Secretary at DHHS, nor the Surgeon General, nor the Director of CDC). Often, it is a state health official, local health official or professional organization.

Let’s look at one of the most basic public health functions – disease surveillance and reporting. Reporting is the first step in preventing and controlling the spread of disease. We need to know about cases before we can take actions. One would think it would be mandatory. Not so. The US National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System or NNDSS) is VOLUNTARY. The CDC role in this system is not voluntary, but is limited to receiving reports from states and publishing the data in an annual report.

Who decides which diseases are to be reported? “Public health officials at state health departments and CDC collaborate in determining which diseases should be nationally notifiable.” Do all states collect data on notifiable diseases? “States and jurisdictions are sovereign entities. Reportable conditions are determined by laws and regulations of each state and jurisdiction. It is possible that some conditions deemed nationally notifiable might not be reportable in certain states or jurisdictions.” This means that our national data and statistics on notifiable diseases are incomplete. Are states required to report notifiable diseases to the CDC? “Although disease reporting is mandated by legislation or regulation at the state and local levels, state reporting to CDC is voluntary”. This means that the state and local governments decide and mandate the data that are to be collected, not the CDC, not the federal government. The CDC works within this voluntary network to assemble and publish the best data it can.

The CDC is fundamentally an information organization. It conducts scientific investigations, analyzes laboratory samples, designs systems for collecting data, prepares and distributes information, publishes reports, and makes recommendations. It has relatively few powers. Authority to close down a restaurant? Local health departments. Authority to close a poultry plant? The US Department of Agriculture. Authority to recall a food item from the supermarket shelves? FDA, and, if it is a meat product, the US Department of Agriculture. What about the authorities to mandate that hospitals train their staff in safe procedures for treating Ebola, or mandate that hospitals maintain supplies of protective gear in the event of an Ebola case? I don’t know the answer to either of these questions, but I am betting that: a) it is different for each state, b) it may not exist in many states, c) the authority, if present, will reside in a hodge podge of state and local sanitation, labor, and health departments (protecting and training staff might be a labor issue as well as a health issue). While the CDC can recommend a certain level of preparedness, it does not have the powers to conduct audits or enforce recommendations. The level of preparedness at hospitals throughout the nation depends largely on decisions taken by hospital administrators to implement CDC recommendations, but there is no process in place to evaluate implementation or to correct inadequate implementation. Our only method of identifying non-adherence to recommendations is the occurrence of a major failure such as the one we have just seen at the hospital in Dallas.

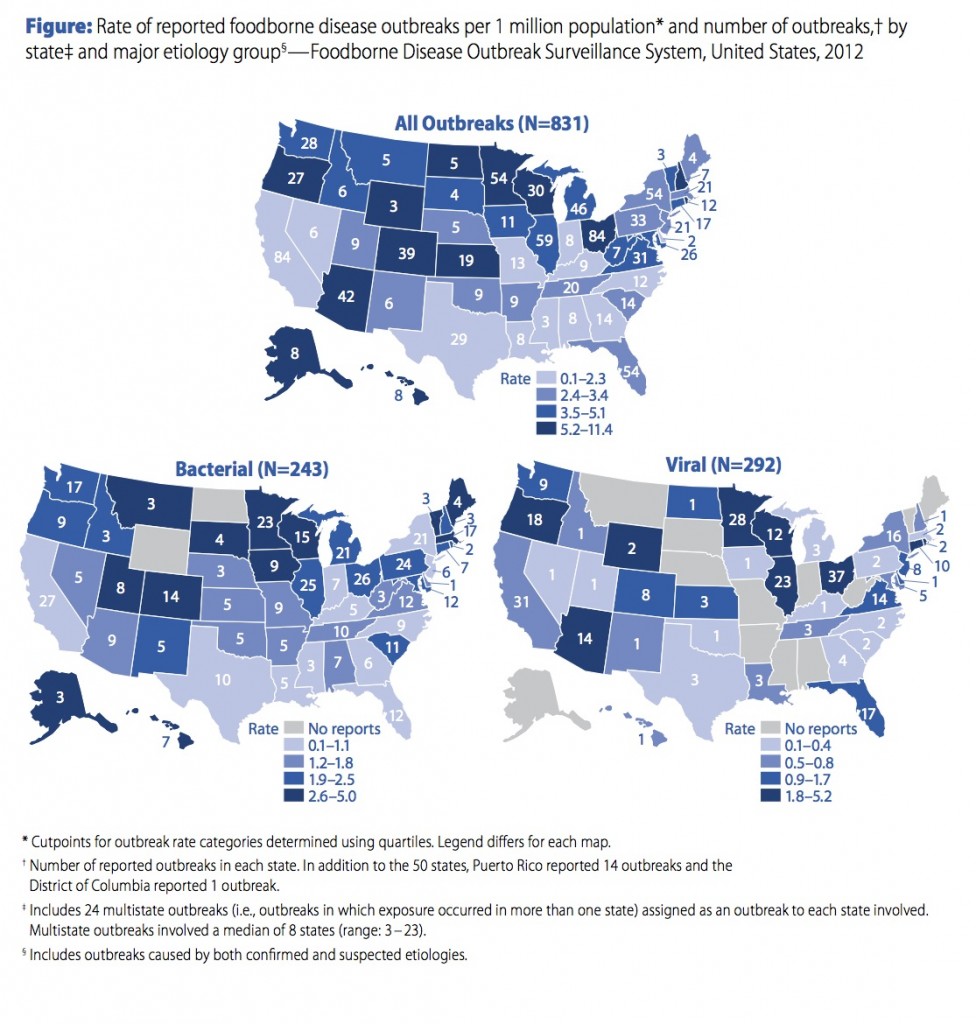

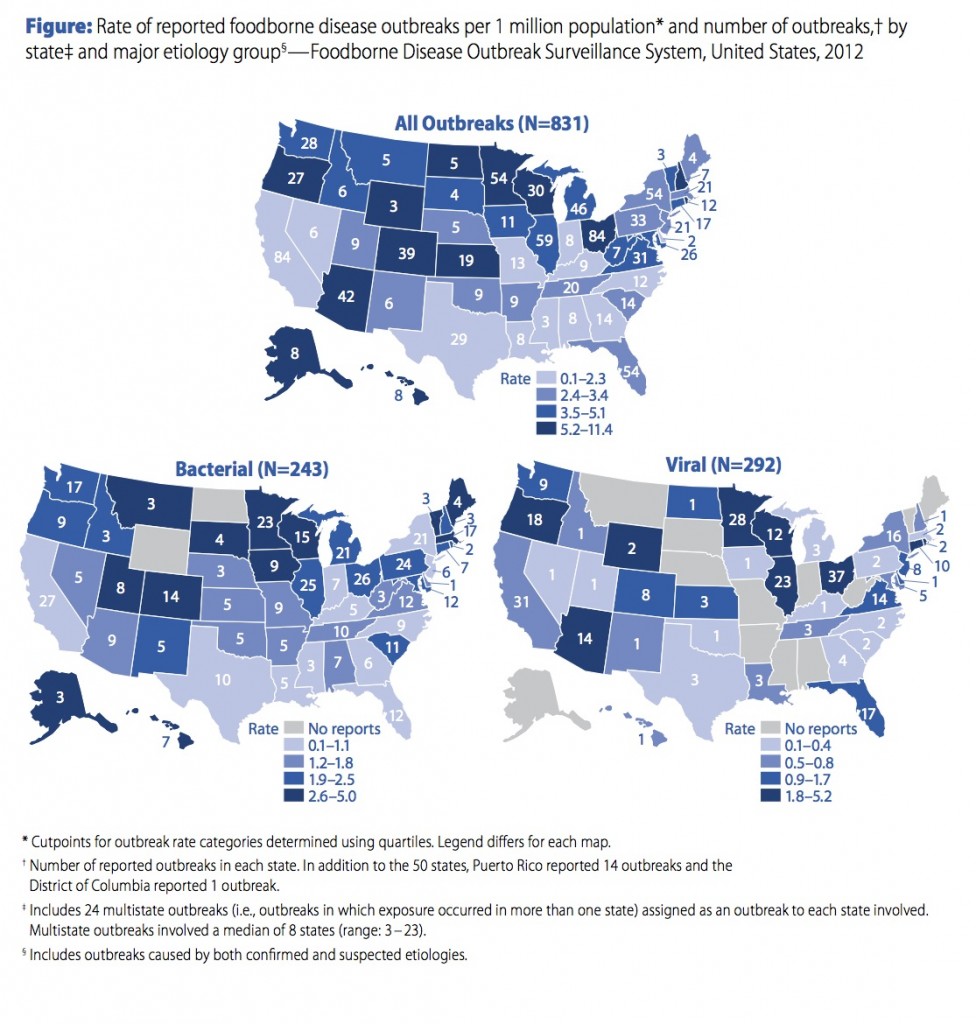

The CDC prestige gives it some level of authority when making recommendations, but we shouldn’t confuse prestige with actual authority. CDC works effectively with states that value its input. In a foodborne outbreak, for example, states have the option of inviting the CDC to help it manage the outbreak – or not. When an outbreak is contained within state lines, the state health department is not required to call on the CDC, and not even required to report the outbreak – and some states don’t. As a result, the US has a calico pattern of statistics regarding foodborne outbreaks. States with strong food safety programs take a proactive approach to tracking down and identifying outbreaks, request CDC assistance with investigations, and report the outbreaks to the CDC; other states do just the opposite. Examine the CDC map that shows foodborne outbreaks by state. States with strong food safety programs have high rates of reported outbreaks! States with weak programs or no interest in reporting show few reported outbreaks. Take the example of Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, three bordering states that are fairly similar to each other. In 2012 Ohio and Illinois each reported 1.8 – 5.2 viral foodborne outbreaks per million (on the high end), but neighboring Indiana reported ZERO! Other states reporting zero viral foodborne outbreaks in 2012 include Mississippi, Missourri, Alabama, Arkansas, and West Virginia. The data reflect reporting behaviors rather than the information we need about occurrence of viral foodborne outbreaks.

Food borne outbreaks, reported by state.

The pattern of fragmentation and decentralization is not limited to data reporting, but is repeated over and over throughout our health care system and public health infrastructure. Let’s not forget that the Supreme Court upheld the rights of states to opt out of the biggest national health initiative of the last 50 years, the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion. The rewards in public health are the rewards of doing interesting and important work. Every CDC employee (or ex-employee) that I have ever known works with amazing dedication and takes their responsibilities with the utmost seriousness. All see themselves as public servants, and I have never heard any of them complain about the lack of resources or any other aspect of their work. Blaming the CDC for our unpreparedness in the face of Ebola is probably the least productive thing we can do right now. Instead, we need to strengthen all the pieces of our decentralized public health network so that every American is protected in times of public health emergencies. Expecting an agency with relatively limited powers, such as the CDC, to be held accountable for failures in a decentralized network won’t get us where we want to be.