A walk through the farmer’s market can be a step on the way to cultural competence.

I visited Gainesville, Florida at the end of October, and my hosts from the College of Pharmacy took me through the local farmer’s market. My attention was piqued by the sub-tropical produce such as persimmons and pecans, items I don’t see at my farmer’s market in New England. Passing up the opportunity to purchase wild boar liver and other wild boar products, I stopped in my tracks when I saw a red, fruit-like thing, exotic and new to me, the calyx of the hibiscus flower. The calyx is a capsule surrounding the seeds, and it is about an inch in diameter.

Photo: Jeff McMillian, used with permission

The hand written sign said, “sorrelle”. Walking further we found more “sorrelle”, also labeled “roselle”, and the stand owners explained that these were used to make a tea similar to the red zinger teas we could buy in the supermarket. From this I inferred that we were looking at hibiscus, and I bought a dried sample to take home with me. Once back home, I learned that the plant has many names. The scientific name is Hibiscus sabdariffa L, but it is also called Roselle, its original Arabic name is Karkade. and other common names are Sorrel, Red sorrel, Jamaica Sorrel, Lozey, Cabitutu, Vinuela, Oseille de Guinee, Pink Lemonade Flower, Vinagrillo, Afrika Bamya, sour-sour and Florida cranberry. The names hint at the many places around the world where it is used to make teas or iced beverages, and it is easy to access recipes for the beverage, including a recipe by Martha Stewart for Hibiscus Iced Tea.

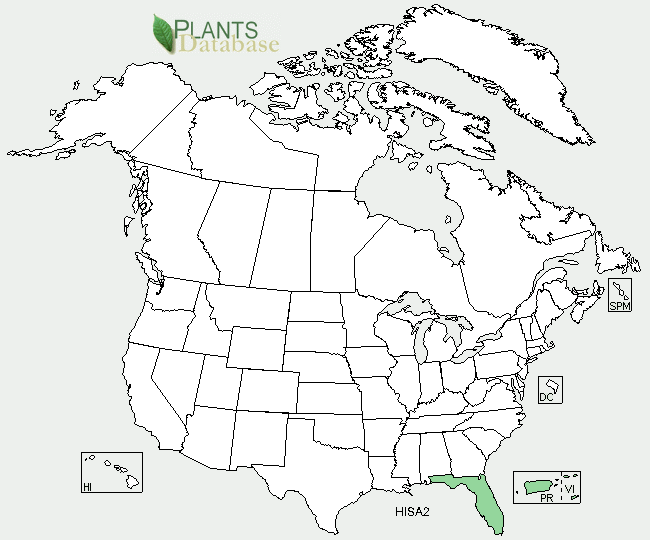

As shown on this US Department of Agriculture map, Florida is the only place in the mainland United States where this plant grows. http://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=hisa2

USDA map showing where H. sabdariffa L grows in the United States.

A number of sources refer to widely held beliefs about the herb’s efficacy in lowering blood pressure, and it is not clear where and when these beliefs arose. Even less clear is the scientific evidence supporting such beliefs. A study funded by the USDA Agricultural Research Service and Celestial Seasonings and published in 2008 reported that hibiscus tea lowered blood pressure by 7.2 in a group of pre-hypertensive and mildly hypertensive adults compared to 1.3 points in a similar group of people drinking placebo beverage. Another USDA funded study confirmed antimicrobial activity of sorrel (Hibiscus sabdariffa) on Esherichia coli 0157:H7 isolates from food, veterinary and clinical samples. It is possible to find other studies about H. sabdariffa L, and its potential effects on blood pressure, and even cholesterol, and this might make an interesting topic for a systematic literature review.

Whether or not there is a biologic effect on health, we are left wondering about the number of people in the area drinking the beverage, as well as their beliefs about the tea. Do people believe that the herb will lower their blood pressure? If so, does this affect their adherence to pharmacologic therapies? We can begin to envision some interesting lines of inquiry. At minimum it might be an interesting way to engage the local community and learn about local customs and beliefs.

Walking around a farmer’s market (or other local sites) is a pleasant way to begin learning about a community, and a nice metaphor for one aspect of cultural competence: Go out into the community you serve, look around, ask questions, taste, learn – repeat!